Introducing Improvisation

This blog first appeared on the ABRSM website, May 2018

I have a clear recollection of my first encounter with a piano, aged 7. My feet could only just touch the pedals, but I could stretch my left hand all the way down to the lowest notes, and my right to the very highest ones at the top. I was immediately captivated by the seemingly infinite possibilities, the combination of high and low, the rich resonance produced by the sustain pedal…

Despite not being a lover of jazz, my teacher Carola Grindea always encouraged creativity at the keyboard, and the sense of freedom I got when experimenting at the piano never left me. I eventually became a professional jazz pianist and teacher, and now have about 30 years experience of helping pupils get to grips with the world of improvisation.

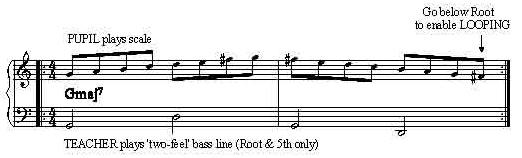

In my opinion, every music lesson should include a ‘fun’ section where pupil and teacher interact, as if playing a duet – but without music. The easiest way to integrate this into a lesson is when teaching scales and arpeggios. Instead of this being a chore, or something learnt by rote, try turning it into a musical dialogue – for instance, accompany the scale by playing a bass line, low down on the keyboard:

Fig 1:

This encourages the student to play in time with you, especially when the scale is ‘looped’ by adding the 7th below the root, keeping it in 4/4 time.

But that’s not all… as soon as he/she can play the scale without needing to read it, remove the music, keep playing the bass line, and suggest that they…

• Play the notes in any order they like

• Start on notes other than the root

• Go down instead of up from the starting note

• Change direction in mid scale

• Experiment with patterns (eg: 123, 234, 456… etc)

• Try playing in ‘swing’ quavers

• Change the rhythm (no need to play continuous quavers)

• Start on the offbeat (eg: the ‘and’ of one)

… and generally aim to turn the notes of the scale into musical phrases – ie: improvise!

To nudge them in the right direction, try introducing another game where you play two bars each, with the student either copying your ideas, or responding to them more spontaneously. Here's an example with a walking bass line and Mixolydian scale:

Fig 2:

Alternating as above gives your pupil some pointers for constructing 2-bar phrases and imposes more of a structure on the conversation. It’s essentially what happens in the final aural test of any JAZZ exam, when the candidate plays with the examiner – the most fun part!

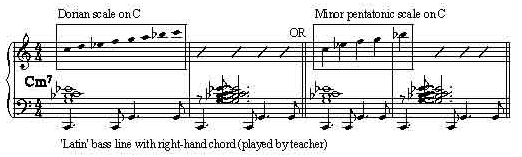

This part of the lesson is also a great opportunity to make connections between scales/arpeggios and harmony. There’s little point in learning (say) a Dorian mode, or a minor pentatonic scale, unless you realize that both of these can be played over a minor seventh chord. You can make this even clearer by playing the chord in your accompaniment:

Fig 3:

Improvisation ‘boxes’ like the ones above appear in all jazz exam pieces, but very often only part of a scale or arpeggio will be given – or it may be ‘disguised’, with the notes shown in a different order. It’s down to the teacher to identify the scale and make the harmonic connection clear.

I hope to give you further tips for interpreting these boxes in a future blog.

Tim Richards is a jazz pianist, composer, bandleader and educator. He is a contributor to the ABRSM Jazz Piano syllabus and has been a jazz examiner since its inception in 1997.

Tim’s next course for piano teachers on the ABRSM Jazz Piano Syllabus is being held at Benslow Music in Hitchin (Herts) from 3 to 6 August 2018. The course is also hosted by The CITY LIT in London over four Sundays in November 2018.

You can read about Tim’s jazz and blues piano books at schott-music.com